-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

CPD & EVENTS

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Decolonising the record

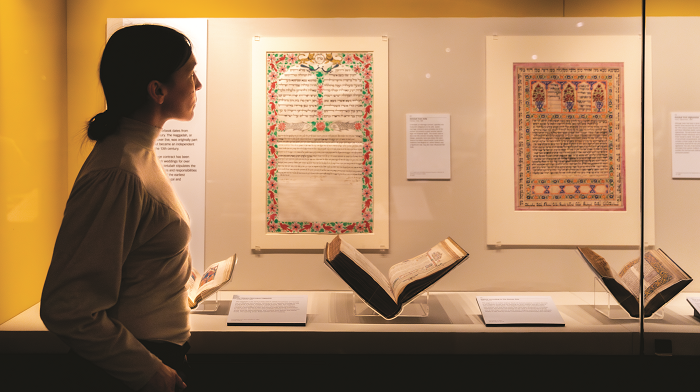

How the British Library is approaching the delicate task of translating their archives.

By Nisreen Alzaraee

Historical records are often problematic in nature, particularly when they originate from colonial administrations. Dealing with such records in translation raises a variety of ethical as well as practical questions. The British Library/Qatar Foundation Partnership (BLQFP) project is digitising material from multiple collections related to the history of the Gulf. These digitised records are published in the Qatar Digital Library (QDL) with enhanced bilingual catalogue descriptions in English and Arabic. The vast majority of the material comes from the India Office Records (IOR), which incorporates the archival records of the English East India Company and the India Office. They span centuries of colonial activity across different continents, cultures and peoples.

In trying to describe this material, cataloguers and translators on the BLQFP recognised the potential for a position of ‘neutrality’ to morph into complicity with the colonial administration. These in-house teams had been grappling with individual questions of terminology for years, but in 2020 there was an opportunity to build on emerging approaches and resources to develop a dedicated and evolving set of guidelines for conscientious bilingual description (CBD).

In the CBD process, potentially offensive and/or problematic terms are identified and thoroughly researched before being categorised into one of four levels: not problematic, sometimes problematic, always problematic, and problematic and offensive. The guidelines then provide recommendations on how to treat the terms in both English and Arabic.

Levels of treatment include using quotation marks and providing additional context in parentheses, and/or adding the term to the QDL’s hyperlinked bilingual glossary to provide more information. The most complex terms require such extensive historical and linguistic contextualisation that they warrant longer-form exploration under the QDL’s expert articles section. An example is ‘Bania’. (Find out more here).

Terms may require thoughtful treatment in either language for a variety of reasons, but some pose particular questions for translation. While the IOR material is predominantly in English, it features words borrowed or adapted from other languages, including Arabic. Two such terms that have generated much discussion are fallāḥ and Mohammedan.

Fallāḥ (pl. fallāḥīn) is originally an Arabic word فلاح،ين فلاحين equivalent to ‘agricultural labourer’ or ‘farmer’. In Arabic, the word also has ethnic implications dating back to the Arab conquest of Egypt when it was used favourably to refer to indigenous Egyptians.

By contrast, when British colonial officials use fallāḥ in the IOR files, it is usually to refer disparagingly to agricultural labourers or their political/social class (a usage closer in meaning to ‘peasant’). Although the word is originally Arabic, a simple back-translation here would misrepresent its usage in the colonial files, introducing a positive or neutral connotation that is not present in the English. At the same time, there is no better alternative word to use in the translation.

While it might suffice in the English description to enclose the term in quotation marks – indicating a direct quotation, and our distance from the colonial administrators’ perspective – the Arabic demanded an additional step. After assessing whether the word had been used in any other contexts across the QDL, the term was added to both the English and Arabic glossaries, thereby providing the necessary historical context on how it is specifically used in these records.

Mohammedan meanwhile is both highly problematic and offensive. Appearing across colonial discourse on Muslims from the 15th century onwards, the word means ‘followers of Muhammad’. Historically, it reflects an antiquated Christian view of Muslims as heretics and/or a conflation of Muhammad’s place in Islam with that of Jesus in Christianity. In the IOR files, British officials use the term to refer to Muslims or anything related to Islam. The inaccuracy inherent in this usage warrants signalling in both English and Arabic.

Tempting as it may be to avoid reproducing the offensive term, to do so would efface and erase the biases and perspectives of the colonial administrators, sanitising and distorting their voices. Instead, we place it within quotation marks, followed immediately by an in-line gloss in square brackets: ‘[Muslim]’ or ‘[Islamic]’. In translation, we similarly use محمديg/ة within quotation marks, followed by [ة/ مسلمn] or [ة/إسلاميn] in square brackets. Glossary entries in both English and Arabic provide additional context on the term’s problematic nature.

With such interventions, we aim to introduce distance between ourselves and the colonial authors of the records. By signalling the language, its connotations and biases, rather than simply accepting and reproducing it, we hope to encourage QDL users in Arabic and English to consider the records more critically. The archive is not neutral, nor is its language. They both reflect the colonial project with its imperialist agendas and prejudices.

Like most scholarly efforts in this area, CBD remains a work in progress. It is evolving and expanding as the BLQFP teams continue to evaluate the content and context of the collections, hoping to set multilingual standards for the ongoing treatment of colonial and imperialist language.

Further information

- Qatar Digital Library (in English and in Arabic)

- Woodbridge, D, Reid, C and Aboelezz, M (2022) ‘Conscientious Bilingual Description: Treating problematic language in colonial records on the Qatar Digital Library’. In Archivoz

- Shamma, T (2018) ‘Translation and Colonialism’. In Harding, S-A and Carbonell Cortés, O (2018), The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Culture Routledge

- Modest, W and Lelijveld, R (2018) Words Matter: An unfinished guide to word choices in the cultural sector, Tropenmuseum

- Wyke, B (2013) ‘Ethics and Translation’. In Gambier, Y and van Doorslaer, L, Handbook of Translation Studies: Volume 1, Benjamins

Nisreen Alzaraee is an Arabic Translator for the British Library/Qatar Foundation Partnership Programme. She holds a Master’s degree in English studies and has years of experience in discourse, analysis, and political and developmental research.

Nisreen Alzaraee is an Arabic Translator for the British Library/Qatar Foundation Partnership Programme. She holds a Master’s degree in English studies and has years of experience in discourse, analysis, and political and developmental research.

Nisreen is co-presenting with Julia Ihnatowicz at the CIOL Translators Day in London in March on ‘Translation at the British Library – Conscientious Bilingual Description’. CIOL Translators Day

This article is reproduced from the Winter 2024/2025 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.