-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

CPD & EVENTS

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Picture book politics

What Andrew Wong learnt from a unique project to translate (in relay) a children’s book based on a political speech

Former Uruguay president José Mujica is known as the world’s poorest president because he donated almost 90% of his salary to the poor. Elected to the country’s top office in 2010, the staunch leftist was a former Tupamaros guerrilla who was imprisoned for about 14 years and released in 1985 after the military dictatorship collapsed. Mujica is also known for his signature outfit – a suit with no tie – and for delivering inspiring speeches using simple language.

Former Uruguay president José Mujica is known as the world’s poorest president because he donated almost 90% of his salary to the poor. Elected to the country’s top office in 2010, the staunch leftist was a former Tupamaros guerrilla who was imprisoned for about 14 years and released in 1985 after the military dictatorship collapsed. Mujica is also known for his signature outfit – a suit with no tie – and for delivering inspiring speeches using simple language.

In Japan, interest in Mujica continues amid a steadily growing number of books and movies, driven in no small part by a picture book that speaks to both children and adults. Translating this book, which features Mujica’s 2012 speech at the Rio+20 World Summit, into English came with the challenge of deciphering his vision, originally conveyed in Spanish, and re-presenting it for a diverse English readership.

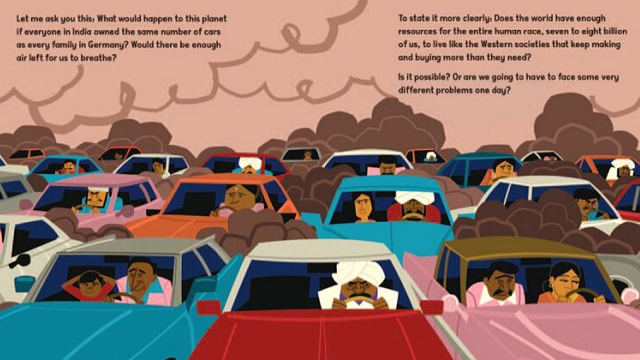

The speech argues that over-consumption by humanity is impacting the environment; globalisation has become a system for making things cheaply somewhere and then moving them across the world to sell them more expensively; common wisdom defines being poor as wanting infinitely more; and politics must change for sustainable development. It leaves us with a path to protect the environment guided by human happiness.

The original speech had been adapted for Japanese children with a focus on the core message – being content with what one has – within the spatial limitations of a picture book. However, the differences between the three languages in the English translation involved another layer of decoding. How the text is understood is influenced by linguistic patterns and cultural perspectives, so the effect produced was balanced with the need for brevity when choosing the right target-language expression. In the opening page, which introduces Mujica, shisso (‘frugal’) is translated as ‘simple’ to draw an effective contrast between his lifestyle/appearance and the ‘presidential palace’ (kōtei; ‘official residence’), where he chose not to live.

An expression that presented a greater challenge was kokoro wo hitotsu ni (‘our hearts as one’), which was invoked on several occasions to express unity in spirit. ‘Solidarity’ and ‘togetherness’ offered a succinct contrast in the part where Mujica questioned unity amid ruthless competition for affluence among individuals and nations.

Mujica argued that the environmental crisis is an outcome of our ‘way of life’ (ikikata) and ‘what we have come to seek to make us happy’ (shiawase no nakami). For shiawase I had several options: joy, contentment, happiness and wellbeing. After much pondering, my editors at Enchanted Lion, Claudia Zoe Bedrick and Kate Finney, and I agreed on ‘shared human happiness’ because it clearly expresses happiness not driven by personal desire but for all humanity.

In the part where he suggests that durable light bulbs could be made, the Japanese language allowed for the repeated use of no desu and dakara (‘because’) to drum home an explanation of how consumption must continue for money to keep flowing and economies to stay afloat. In English, we chose to use ‘such’, as in ‘we cannot make such things’ (i.e. things that last) and ‘such is the culture of our civilization’ (i.e. production/ consumption-driven), for emphasis here.

Negotiating three languages

Working from an adapted version sometimes also calls for reference to the original. In the Japanese version when Mujica acknowledges the efforts of his peers he seems to want to express respect (kei-i wo arawashitai) for building consensus (iken wo matomeyō to suru koto), which does not flow well with the spontaneity of the original.

Knowing how Japanese can sometimes be verbose for the purpose of courtesy, I welcomed Kate’s suggestion of ‘respect our agreements’, which fits perfectly. Unable to understand the nuances of the Spanish text, I relied heavily on her numerous notes, especially for vital changes to the tone of voice, such as when Mujica refers to humanity’s ‘aggression toward nature’ rather than to kankyō no akka (‘the worsening environment’).

It was important to capture Mujica’s voice. In his original speech he speaks forcefully at times, sounding angry, as if he is delivering a wake-up call to his fellow leaders. This contrasts with the Japanese version, and indeed the Traditional Chinese translation, where Mujica is portrayed as a grandfather figure who shares his wisdom with the younger generation.

The closing statement posed a different problem. Mujica ended abruptly, saying his thanks before storming off, leaving listeners to grapple with his parting words: Cuando luchamos por el medio ambiente, el primer elemento del medio ambiente se llama la felicidad humana. Having already planted the notion of happiness for all humanity, we shaped this into ‘If we appreciate the beauty of nature and life itself and care for our world, we will be able to live well as humans on this planet.’ This ties up the various ends of his argument for reining in over-consumption to protect the environment.

Working with pictures

The text works with Gaku Nakagawa’s illustrations to interpret Mujica’s ideas. My favourite spread is the baby in the cosmos. Mujica’s brief mention of how life passes in a blink of an eye and how nothing is more valuable was reorganised and expanded to convey the sense of being born into this world to find happiness. This then turns straight into a picture of an adult frantically pedalling away on the gears of the economy, trying to escape the menacing claws of a monster; no hint of happiness there.

There was also some visual adaptation, as Enchanted Lion and I identified some problematic representations. For example, the image of traffic had only scowling men at the wheel. Nakagawa readily changed this to include women driving, smiling faces and children too. The latest editions of the Japanese version have adopted these new images, with the picture of the happy family near the end symbolic of happiness for humanity in the text.

Mujica’s unifying message and humbling view of human existence first kindled Japanese editor Yoshimi Kusaba’s desire to share the speech with children, which in turn sparked my desire to share his vision with English readers. More than just a job, I believe it contains a meaningful and important message for posterity. As the pandemic exposes social inequities, it is time to talk about a system that lets us be guided by a new approach to happiness.

This article was adapted from a presentation for SCBWI Japan Translation Days 2020 (japan.scbwi.org).

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.