-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Professional Membership

- Affiliate Membership

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

LANGUAGE ASSESSMENTS

- English

- All Other Languages

-

CPD & EVENTS

- Webinars & Events

- CIOL Conferences

- Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist Magazine

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

The Urdu tapestry

Kashif Khalid traces the history, art and poetry of the language

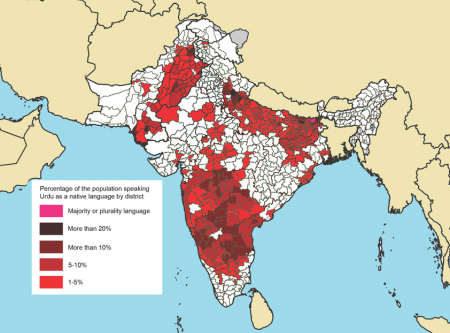

According to 2022 estimates, Urdu is the tenth most widely spoken language in the world, with 230 million speakers, including those who speak it as a second language. The national language of Pakistan, it is widely spoken in India, as well as in various countries worldwide, including Afghanistan, Bahrain, Botswana, Fiji, Mauritius, Nepal, Norway, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Thailand and the UK. Yet it receives considerably less attention globally than many other major world languages.

An Indo-Aryan language, it shares close ties with Hindi, and speakers of the two languages can understand each other. Both stem from the Khari Boli language and are known collectively as Hindustani – the lingua franca of Northern India. Though Standard Urdu and Standard Hindi exhibit few significant differences, linguists recognise them as distinct formal registers primarily due to their widespread usage across different regions (dialects are usually confined to smaller areas) and the fact that their written forms are not mutually intelligible. While Urdu is written in the Nastaliq script and draws vocabulary from Persian and Arabic, Hindi is written in the Devanagari script and incorporates more Sanskrit words.

Emergence from Old Hindi

Urdu underwent significant transformations during the Islamic conquests of the Indian subcontinent from the 12th to the 16th centuries. Its early form, known as Hindavi or Old Hindi, was spoken in Delhi and its surrounding regions, and was written in the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaliq style. As settlers integrated and mingled with the local population, the modern language began to emerge.

Persian became the official language of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857), leading to the integration of Persian vocabulary into Urdu, alongside loanwords from Arabic and Turkish. This era witnessed the emergence of several monikers for the Urdu language, including Rekhta and Hindavi. The term Urdu is derived from the Turkish word Ordu, which originally signified ‘horde’ or ‘army’, denoting the language spoken by soldiers and traders in the region.

From the 13th century, authors started using Urdu in literature and poetry. Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), a distinguished scholar living under the Delhi Sultanate, played a pivotal role in its development. Earning the title the Father of Urdu Literature, he wrote in Persian and Urdu, and contributed significantly to the flourishing of Urdu in courtly and aristocratic contexts. As a result, the learning of Urdu became more widespread.

Today, Urdu encompasses four mutually intelligible dialects: Dakhini, Dhakaiya, Rekhta and Modern Vernacular Urdu. Dakhini is spoken in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh; Dhakaiya in Bangladesh, although its usage is diminishing; and Modern Vernacular Urdu in cities such as Delhi. Rekhta serves as the language for composing poetry.

Golden literary age

The golden age of Urdu literature, spurred by the reign of Emperor Akbar in the 16th century, continued to flourish into the 18th and 19th centuries. Renowned poets like Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810), hailed as the God of Urdu Poetry, emerged. His ghazals (a form of poetry unique to the Indian subcontinent) continue to be celebrated for their timeless beauty. Mirza Ghalib (1797-1869) left an indelible mark on Urdu poetry. His verses, a captivating blend of classical Persian and Indian styles, explore themes of love, loss and the complexities of human existence.

The arrival of the British Raj in the 18th century marked a new chapter in Urdu’s evolution. While English gained prominence in official spheres, Urdu became a powerful tool for dissent and a symbol of cultural identity. Poets and intellectuals like Allama Iqbal (1877-1938) and Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911-1984) wielded the pen as a tool of resistance, using Urdu to express their yearning for freedom and social justice. Iqbal’s poetry continues to inspire generations with its call for self-discovery and national awakening, while Faiz gave voice to the marginalised through his revolutionary verses, challenging societal inequalities and advocating for a just world.

A script from ا to ئ

Beyond its historical significance, Urdu is appreciated for its inherent musicality and nuanced expressions. The Nastaliq script, with its flowing lines and artistic flourishes, adds a visual beauty. Nastaliq is an extended version of the Perso-Arabic script with additional characters to accommodate sounds specific to Urdu. Its 37 letters include:

ا The first letter of the Nastaliq alphabet, pronounced like the ‘a’ in ‘father’ (Alif/A)

ت Pronounced with a gentle ‘t’ sound (Te/T)

ث Mirrors the English ’s’ with a slight hiss in its pronunciation (Se/S)

ج Pronounced similar to an English ‘j’ (Je/J)

ح Resembles the English ‘h’ with a breathy quality (He/H)

خ A sound not present in English, resembling the German ‘ch’ in ‘Bach’ (Khe/Kh)

د Corresponds to ‘d’ in English, providing a crisp, clear sound (Dal/D)

ذ A buzzing sound similar to English ‘z’ (Zal/Z)

ر Mirrors the English ‘r’ sound with a slight roll of the tongue (Re/R).

In today’s interconnected world, Urdu extends its reach beyond the Indian subcontinent and Pakistan. Its influence is evident in global art, literature and cinema, from the soulful renditions of ghazals to the captivating dialogues of Pakistani films.

Kashif Khalid MCIL is a seasoned linguist with over five years of experience in the localisation industry. Specialising in English to Urdu, Punjabi and Hindi, he is passionate about languages and AI technologies, and continuously explores innovative solutions in the translation industry. He is committed to bringing texts to life for diverse clients.

This article is reproduced from the Autumn 2024 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.