-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

EVENTS & TRAINING

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- CIOL Conference Season 2025

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Covert communication

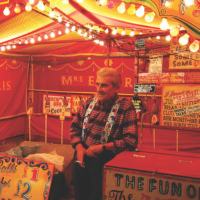

Covert languages often start with children, as with the M language in Malaysia

What the clandestine M language of Malaysia can tell us about secret languages around the world

By Norhaniza Nuruddin

The phenomenon of hidden languages is truly intriguing. These confidential communication methods often develop within groups, serving purposes ranging from playful encoding to secretive exchanges. Some studies suggest that the use of a secret language is quite prevalent among twins.1 Why twins? It is thought they use communication to isolate themselves from others. This same idea applies to all secret languages; we use them within our own circle, keeping them exclusive and unintelligible to outsiders.

The secret ‘M’ language (Bahasa M) transforms Malay phrases through the addition of ‘shadow syllables’. Exemplifying how linguistic creativity can be employed to create a secretive linguistic code, the M language alters familiar phrases by inserting syllables, thus obscuring the meaning to those unfamiliar with it. The transformation of Saya lapar (‘I am hungry’) into Samayama lamaparmar showcases how the systematic addition of syllables creates a new linguistic form that retains a semblance of the original.

Less prevalent than the M language, the ‘F’ language is a further example of this covert communication method. In the F language, Saya lapar would be rendered as Safayafa lafaparfar. Different communities may tailor their own versions to suit their needs.

One of the fascinating aspects of secret languages is their oral nature, as they rely heavily on pronunciation and rhythm for comprehension. When spoken rapidly, the encoded phrases take on a distinct sound, almost resembling a foreign language. One example, Jamadimi, samayama nakmak tamannyama jimikama amadama yangmang imingatmat bamahamasama M iminimi? (‘So, I want to ask if anyone remembers this M language?’), reveals the rapid and fluid nature of communication within the secret language.

Although it originated among the Malay-speaking community of Malaysia, the M language was taken up and adapted by some English-speaking citizens. An English phrase like ‘Do you want to go to the concert?’ may be transformed into ‘Domu youmu wantman tomu gomo tomu theme conmonsertmert’. Decoding this version in writing is more complex as the shadow syllables are intricately tied to the pronunciation of the words.

Coded languages worldwide

The concept of secret languages is not unique to Malay speakers. Throughout history, various communities have developed their own clandestine communication methods, often as a means of maintaining privacy or exclusivity. These languages can be found across different linguistic and cultural backgrounds, each reflecting the unique characteristics and needs of the community that created them.

In some cases, they emerge as a kind of defiance against oppressive forces. During periods of cultural suppression or political turmoil, marginalised communities may invent ways of evading censorship or surveillance. These secret languages serve not only as a means of preserving cultural identity but also as a form of resistance against attempts to silence or control linguistic expression.

In addition to their practical applications, such cants play a role in fostering a sense of belonging within the community. The shared knowledge of the code creates a bond among its speakers, fostering a sense of solidarity and mutual trust. In this way, they serve not only as a tool for communication but also as a marker of group identity. As for M language, it is intended as a secret means of talking to close friends or siblings.

Despite their inward nature, such languages often attract curiosity and intrigue from outsiders. Linguists and researchers may study them to gain insights into the underlying mechanisms of language and communication. Additionally, popular culture often romanticises the concept of secret languages, portraying them as mysterious and exotic.

According to Listverse,2 the Top 10 secret languages worldwide include Swardspeak, Pig Latin, Thieves’ Cant, Carnie and Polari. Among these, Pig Latin, which is based on the English language, shares similarities with the M language. First employed around 1869 by children, Pig Latin involves converting English words based on their initial letters or groups of letters. If a word begins with a vowel, ‘way’ is appended to the end, so ‘awesome’ becomes ‘awesomeway’. If it starts with a consonant followed by a vowel, the initial consonant is relocated to the end with ‘ay’, so ‘happy’ becomes ‘appyhay’. In cases where the word starts with two consonants, both are shifted to the end, as when ‘child’ becomes ‘ildchay’.

Lunfardo is used by prisoners in Argentina and started among the poorer people in Buenos Aires. Mixing Spanish and Italian, it has more than 5,000 words and is known for switching syllables, e.g. feca for cafe. It was used in tango music until 1943, when it was banned from tango because of its association with violence and sex. In the 1960s it made a comeback, and you can now find Spanish-Lunfardo dictionaries.

Wrestlers, meanwhile, have Carnie, which began with carnival workers who wanted to communicate during fake wrestling matches without the audience catching on. In Carnie, English words are changed by adding ‘eaz’ before each vowel sound. So, ‘is’ becomes ‘eazis’ and ‘Kelley’ becomes ‘Keazelleazey’. There are also special words such as ‘Andre shot’ (making a wrestler’s muscles look bigger in photos); ‘Batman match’ (a boring match); ‘beat down’ (when a wrestler gets attacked by a group); and ‘canned heat’ (fake crowd noise, e.g. cheering, played through speakers).

Wrestlers, meanwhile, have Carnie, which began with carnival workers who wanted to communicate during fake wrestling matches without the audience catching on. In Carnie, English words are changed by adding ‘eaz’ before each vowel sound. So, ‘is’ becomes ‘eazis’ and ‘Kelley’ becomes ‘Keazelleazey’. There are also special words such as ‘Andre shot’ (making a wrestler’s muscles look bigger in photos); ‘Batman match’ (a boring match); ‘beat down’ (when a wrestler gets attacked by a group); and ‘canned heat’ (fake crowd noise, e.g. cheering, played through speakers).

The image above shows Carnie speaker Albert Harris at his coconut shy at Cambridge Midsummer Fair

Secret languages exemplify the rich diversity of human linguistic creativity. They serve various functions within their respective communities. While specific to their cultural contexts, these cants reflect universal human tendencies towards linguistic innovation and social unity. As researchers continue to explore the fascinating world of secret languages, they uncover the complexities of language mechanisms and the enduring human desire to connect and communicate in meaningful ways.

Notes

1 Thorpe, K et al (2001) ‘Prevalence and Developmental Course of Secret Language’. In International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 36,1, 43-62

2 Taylor, O (2017) ‘Top 10 Secret Languages’. In Listverse, 1/4/17; https://cutt.ly/DezZ6Ccv

Norhaniza Nuruddin ACIL is a certified translator from Malaysia with over 11 years’ linguistic experience.

This article is reproduced from the Autumn 2024 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.