-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

TRAINING & EVENTS

- CIOL Conference Season 2025

- CPD, Webinars & Training

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

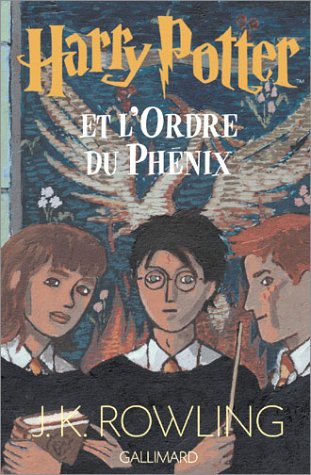

The translatability of Harry Potter

By Miranda Moore

Originally published in The Linguist 39/6, December 2000

In celebration of the 20th anniversary of the first Harry Potter publication, we are pleased to reproduce an article from The Linguist in December 2000 on the challenges faced by translators of JK Rowling's bestselling books, now translated into over 60 languages.

Nieves Martin and her husband, writer Adolfo Munos, are newcomers to translation — with no formal qualifications they broke into the business when Adolfo's publisher, Emece, needed a translator. When their second contract turned out to be a global bestseller, they must have felt charmed. The husband and wife team took over the translation of Harry Potter, JK Rowling's blockbuster series about a boy who found out he was a wizard, in February 1999. Since then Harry Potter has left the world of children's fiction and moved into the adult market as Pottermania has taken hold.

Nieves Martin and her husband, writer Adolfo Munos, are newcomers to translation — with no formal qualifications they broke into the business when Adolfo's publisher, Emece, needed a translator. When their second contract turned out to be a global bestseller, they must have felt charmed. The husband and wife team took over the translation of Harry Potter, JK Rowling's blockbuster series about a boy who found out he was a wizard, in February 1999. Since then Harry Potter has left the world of children's fiction and moved into the adult market as Pottermania has taken hold.

The series has captured the imagination of millions, pulled at the purse-strings of parents the world over, and been almost constantly in the British top ten since 1998. Overseas publishers are eager to cash in on the action and demand for translations has been immense. But Rowling, who speaks Portuguese and has a degree in French and Spanish, has been too busy writing the screen play and fifth book to get involved.

For the translators the task has not been easy — peppered with made-up words, magic spells, regional accents, unknown creatures, and descriptive names, Harry Potter represents a translation minefield. In October it was reported that French translator Jean Francois Menard had suffered a breakdown. He had been working ten hours a day for 63 consecutive days on Harry Potter and the goblet of fire, translating the entire 1,081 pages (French version) in just two months. The desire to deliver the goods quickly is understandable — a delay in China saw poor bootleg translations hit the streets — but it does raise questions about the quality of translation.

According to Nieves Martin, it can take a month to translate one of Rowling's invented words with the degree of humour and subtlety of association contained in the original: "We eventually translated 'skrewts' [magical creatures] as escregutos, which sounds a bit frightening and suggests excrement and sputum". Considering they had four months to translate all 180,000 words of book 4 it is not surprising they left most made-up words as they were — a sad loss for the Spanish-speaking audience.

The words and names have special connotations for a British audience: 'Privet Drive', where Harry lives with his mean relations, conjures up an image of middle-class suburbia; 'Severus Snape', the name of Harry's potions teacher, suggests a nasty, conniving man; and 'Muggle', the word for non-magical person, sounds like a rather foolish 'muddled' individual. For Menard, it was important that these names and words should mean something in French, so that such associations would not be lost. He translated 'muggle' as moldu from the French word mol, meaning 'soft'. "The idea is that people who are moldu are a little soft in the brain".

The Harry Potter series is founded on an English literary tradition of boarding school antics, lashings of adventures, and a hearty appreciation for honest English grub. Menard found the number of references to English literature problematic: "Filch's cat, Mrs Norris, is a character in Mansfield Park.... In English it's funny, but in France nobody knows Jane Austen's character. Mrs Norris is horrible so I gave the cat a French name, Miss Teigne, which means someone very nasty."

The school for wizards, 'Hogwarts', invokes nostalgia for old-fashioned British educational establishments, with a hubble-bubble-warts-and-warlocks coating. Rowling refines the illusion of old English wizardry with an integral alliteration of 'h's -'Hagrid', 'Hermione', 'Hogwarts', 'Harry', 'Hedwig' — long associated with the wizarding world. It is a device that runs through the books, which Menard tried to recreate. "I generally try to stay close to her sound" he explained. "There is a chapter called 'Weasleys' Wizard Wheezes' which I translated as farces pour sorciers facetieux, so you have the s-s-s sound instead of the z-z-z sound in English." In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Fred and George invent 'ton tongue toffee' which makes the tongue of Harry's despicable cousin, Dudley, swell to enormous proportions. "I translated it Praline longue langue, ('long-tongue-praline') so I had the sound 'lin-long-long' that was close to 'ton-ton-to'."

Characters' accents also had to be conveyed. "It is difficult to give a character an accent in French without being silly, because accents are very strong here." The accent of Hagrid, a misguided and heavy-footed giant, is hard to define — it originates somewhere in northern England — so Menard gave him a friendly and simple way of speaking. But when the pseudo-French school Beauxbatons 'arrived' in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire the problem became more complex. For Menard: "It was impossible to translate because you cannot write French with a French accent". So Menard gave the characters certain ways of speaking instead. "Madame Maxine is a snobbish French woman so she speaks in a very precious way" Menard laughs. "Fleur has a traditional French arrogance" so she speaks with an incredulous tone of voice.

The stereotypical French characteristics are captured with typical attention to detail: "It's very French!" Menard said about Fleur's manner. In contrast the rest of the series can only be described as 'very English'.

In part it is this English ness that makes the series so successful — it has a quaint honesty that has appeal across the world — but it does assume readers are familiar with customs unknown to overseas audiences. Translators have two options -to de-Anglicise the text or include explanations of particularly difficult concepts. Most have opted for the latter. In the French version, Ron tells Harry about the house system. Menard explained: "It is the first time he's been to that kind of school so he doesn't know what houses are, but in fact it's the French reader who doesn't know." The Spanish version explains Christmas crackers, prefects and Halloween, and even Harry Potter's US publisher made changes: a strange Anglo-American translation changes 'spellotape' to 'scotchtape' and 'cracking' to 'spanking good' — an obvious attempt to maintain the olde English ambience of the text.

For Menard it was impossible to Frenchify the books. "I wanted to keep it very British and make the readers understand they are in Britain." The first novel begins in the very English-sounding 'Privet Drive', so "the first contact with Harry Potter says 'you are in England'." He translated invented words and names in a sort ofanglicised French: 'Snape' became Rogue, 'Slitherin' became Serpentard and 'Bagman' became Verpey from the acronym VRP, describing someone who sells bags. "'Verpey' could be a name in English" he explained, "but in French the pronunciation is 'verpay' or VRP, which is a bagman."

Occasionally Menard's translations of invented words miss the point: he translates 'Hogwarts' as Poudlard dice of pig') because "'Hogwarts' is a joke on 'warthog'", but the associations a British reader would make are more complex. Crucially, though he maintain the series's sense of humour.

German translator Klaus Fritz often found it impossible to translate Rowling's puns — the magical street name 'Diagon Alley' (try saying it aloud) became Winklegasse or 'Corner Alley', losing the play on words. So Fritz took a broader view of the books to reproduce the same flow of jokes, sometimes inventing new gags to make up for the ones lost in translation. "I found some puns in German that were not possible in English", he said, citing the example of a witch who gets lumbago in the fourth book. In German 'lumbago' is Hexenschuss — meaning literally 'shot of a witch' — a ready-made German pun.

But it would be foolhardy to stray too far from the original text Harry Potter represents a translation minefield.... it can take a month to translate one of Rowling's invented words — Harry Potter is an incomplete series and tiny details are likely to be of vital importance in future books. Rowling's unpublished stories are closely guarded secrets and translators have no means of contacting her to check their translations for possible discrepancies. The Spanish translators have already had to perform a minor U-turn: they had translated 'Professor Sinistra' as (a masculine) Profesor Sinistra, and had to make a quick gender change to Profesora Sinistra when they found her dancing with Mad-Eye Moody in book four.

Perhaps it is fear of future complications that has led most translators to limit the scope of their translations.

But in failing to translate names and words in a meaningful way, or maintain literary devices such as accents, alliteration and word plays, many of these translations lose much of the humour and depth of the original. Maybe we will have to wait until the series is complete and translators can work at leisure, before we see new versions on the shelves that reach their full potential.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263.