-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

EVENTS & TRAINING

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- CIOL Conference Season 2025

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

Shifting the landscape

Translating her grandfather Shemsi Mehmeti’s novel, R B Castrioti learns what translation can reveal about ourselves, and others

Translation is an art – a delicate weaving of two worlds with threads that are at once fragile and unbreakable. It requires a translator to wrestle with the ‘untranslatable’, to balance fidelity with artistry, precision with poetry. This tension lies at the heart of my current project: bringing Bijtë e Tokës së Djegur (Sons of the Scorched Earth) by Shemsi Mehmeti (né Castrioti) – my grandfather – into the English language.

This novel is a landscape of loss and longing, shaped by the idioms and rhythms of a people whose history clings to every syllable. Translating it feels like trying to carry water cupped in both hands, knowing that no matter how carefully I tread, some will inevitably slip through my fingers. Take the Albanian word mall, for instance. Within its single syllable lives a universe – a longing so profound it becomes grief for what is no longer or what, perhaps, never was. How does one carry such a weight into English? I am considering using the phrase ‘There was a lament in his soul’ to express the deep, aching desire for something unattainable, though ‘yearning’ or ‘pining’ might be more fitting. None of these words, however, fully captures the grief embedded in mall, so I may rely on the surrounding text to convey its full emotional weight.

Every page of this novel presents a fresh challenge. There are idioms tied to Albania’s harsh landscapes, silences laden with unspoken truths, and cultural nuances that defy straightforward translation. It is here, in the spaces where languages refuse to align, that the translator must become an artist, sculpting the ineffable into a shape the reader can hold.

Consider the phrase Qëndro o Sokol Llapi, se burrat nuk lodhen për gjumë. Translated literally, it reads: ‘Stay strong, Sokol Llapi, men don’t grow tired for sleep.’ On the surface, it seems like a father’s reproach to his son. Beneath that, however, lies an Albanian cultural ideal: resilience and fortitude in the face of hardship. Rendering this in English requires careful negotiation to preserve its essence while ensuring it resonates with a different audience.

Similarly, expressions like Hana nuk la pa e qortuar të shoqin (‘Hana spared no reproach for her husband’) carry more than their literal meanings. I translated it as ‘Hana made sure to reprimand her husband at every turn’, which conveys the same sense of unflinching criticism, reflecting the cultural expectation of the time, while making it feel more natural to an English-speaking audience. These phrases whisper of familial dynamics and shared histories, of societal norms that bind individuals to a collective understanding. Translating them demands cultural fluency and a deep reverence for the original text.

Linguistic hurdles

The Albanian language presents its own unique hurdles. Shaped by centuries of history and isolation, it is rich with idioms and expressions that resist neat unpacking into English. Some words, like mall, carry layers of meaning that defy direct translation. Others thrive in what is left unsaid, in the spaces between words. Translating these nuances often feels like trying to explain a dream: perfectly coherent in its native form, but prone to unravelling in the retelling.

Consider the phrase bëj kujdes (lit. ‘be careful’). While this might seem straightforward, in Albanian it is often used in situations where there is an emotional subtext – a warning given with love or concern, one that suggests ‘I care about you and I don’t want you to get hurt’ or ‘I hope you are making the right decision’. The English translation loses the tenderness and deeper layer of emotional investment; it can come off as neutral, even dismissive.

Even the structure of Albanian resists translation. Sentences curve and stretch like mountain roads, weaving together ideas that English demands be broken into smaller, more linear pieces. In my translation, I’ve mostly kept sentences longer to capture the flow of the original, and sometimes broken them to fit English’s more straightforward style – always trying to balance clarity with the original complexity. These extended sentences, though perhaps unnatural in English, are necessary to maintain the rhythm and cohesion that Albanian allows for.

Idioms that are tied tightly to the land and its people lose their breath when carried too far from home. One such idiom is E ka zënë korrja në këmbë, which literally means ‘The harvest caught him standing’. It refers to someone who worked tirelessly until their final moment, evoking the image of a farmer passing away while still tending the fields. It symbolises a life of relentless effort, deep ties to the land, and the idea of duty persisting until the very end. In English, we might say ‘He worked himself to the bone’ or ‘He kept going until his last breath’, but these lack the poetic weight of the original – the idea of nature itself marking the end of one’s life.

Cultural context adds another layer of complexity. Albania’s history of occupation, isolation and resilience has infused its language with historical undertones, and sometimes the very act of translation feels like a betrayal – not of the text but of the world it represents. How do you translate the weight of a phrase that carries centuries of struggle? These challenges make every success, no matter how small, feel like a triumph.

A minor breakthrough was finding the right phrase for E ka zemrën copë-copë (lit. ‘His heart is in pieces’). In Albanian, it conveys a deep, unspoken sorrow – grief so profound it feels irreparable. English offers phrases like ‘His heart is broken’ but they lack the rawness and fragmentation of the original. After much deliberation, I settled on ‘His heart was shattered beyond mending’. It is not a perfect match, but it carries the weight of the original.

Familial responsibilities

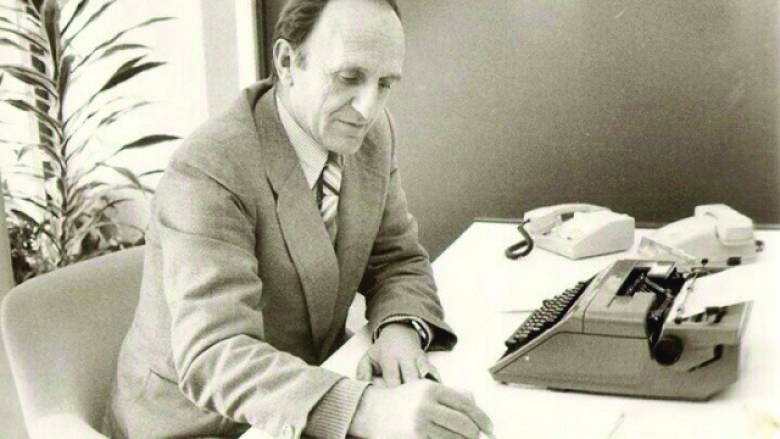

Translation is an act of preservation – a conversation across time and space with the words on the page and the world they came from. Every decision is a negotiation, a question of how much you can bend without breaking the thread. At the heart of this translation lies my grandfather. As I work, his voice seems to echo through every line. This process has brought me closer to him in ways I never expected. He died when I was 22, and though I rarely visited him in Kosovo, our connection always felt unshakable, as if some part of his mind imprinted itself onto mine.

He was the first in our family to attend university – a visionary who brought education to a small, insular country starved of information, freedom and opportunity. To the outside world, he was an award-winning journalist and editor who was committed to revitalising the Albanian language at a time when its usage was prohibited. Known for his work with Rilindja newspaper, he worked tirelessly to bridge gaps, to illuminate truths. His influence shaped me long before I understood it.

Six days after my 22nd birthday, I visited him in Kosovo as he lay in bed, dying of cancer. “Rona,” he whispered when he saw me, his face lighting up. “I missed you.” He struggled to sit up, motioning me closer. “When I die, I want you to have something of mine. No one knows about it, not even your father. Behind the library cabinet, there’s a safe. A hidden hole. Inside, I’ve kept some special things for you. You’ll know what to do with them.”

At the time, I didn’t think much of it. Life moved forward. It wasn’t until 2019 – three years later – that I returned to Kosovo. Behind the cabinet, just as he’d said, I found the safe. Inside was a treasure trove: unpublished manuscripts, secret notes, documentation of his undercover work, writings in Arabic and Russian, old Albanian poetry, and clippings of Rilindja articles he’d deemed significant. Among them was his novel, the one I now translate, along with photographs of him with Polish writers in the 1970s.

In that moment, I knew what I had to do. For years, I had wavered, unsure of my purpose. But there, in his words, I found it. Translating his novel has given me a glimpse into the man he was – his humour, his wisdom, his profound love for the land and its people. It feels like I am having a conversation with him, one that transcends time.

There are moments when I agonise over a single word, rereading passages endlessly, wondering if I’ve lost something essential. There are nights when the weight of responsibility feels too heavy, when I fear I will misstep and fail to do justice to his legacy. And yet, there are also moments of pure joy – the spark of finding just the right phrase, the satisfaction of crafting a sentence that carries the same emotional resonance as the original.

This process has taught me that translation is about empathy – stepping into the mind of the writer, understanding their world and carrying their voice forward. It is an act of preservation, yes, but also an act of creation. Each choice a translator makes shapes how a story will be received, how it will live in a new language.

This project is profoundly personal. It preserves my grandfather’s voice. Through his words, I have discovered not only who he was but also more about myself. Translating his novel feels like building a bridge – not only connecting languages but uniting generations. It is my way of expressing gratitude and saying thank you.

R B Castrioti is a distinguished composer, writer, and the founder and Director of Rilindja International, dedicated to research, cultural preservation and the global dissemination of Albanian and Kosovar literary works.

This article is reproduced from the Spring 2025 issue of The Linguist. Download the full edition here.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.