-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

EVENTS & TRAINING

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- CIOL Conference Season 2025

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

The Linguist in Chinese - Showcasing student translation skills

The Linguist Editorial Board member Professor Binhua Wang invited several MA translation master’s students in Chinese to translate one feature article from each of the four issues of The Linguist in the past year. Each translation has been translated by one, then revised by another, and then proof-read by their translation tutor.

Binhua’s initiative seeks not only to inspire these master’s students, but also to encourage other young linguists and perhaps their tutors, or indeed, other CIOL members to translate an article from The Linguist. Binhua’s hope is to inspire others to translate an article to promote translation skills, create opportunities for learning and to generate a wider readership for the excellent writing in The Linguist, as well as greater impact for CIOL more generally.

拥抱变化,携手破局

As remote interpreting platforms start to offer AI services, Jonathan Downie outlines how interpreters might respond

随着远程口译平台开始引入人工智能服务,乔纳森·唐尼(Jonathan Downie)简述了口译员可能采取的应对方法。

Translators:徐璇,徐涵菲,付添爵(南昌大学)Xuan Xu, Hanfei Xu, Tianjue Fu

Conference interpreting was in shock. At the start of 2023, KUDO, a leading remote interpreting platform, announced that they had launched “the World’s first fully integrated artificial intelligence speech translator”. Many interpreters were furious. It seemed that a platform built to offer them work had now created a service that would take work away. Despite demos and reassurances, doubts remained.

会议口译界一片哗然。2023 年初,代表性远程口译平台 KUDO 宣布推出了“全球首个完全集成式AI语音翻译系统”。这一消息引发了众多口译员的强烈不满:一个原本为译员提供工作的平台,却在开发一项加速他们失业的服务。尽管KUDO做了使用演示,并对译员做出了相关保证,疑虑依然挥之不去。

Later, another remote interpreting platform, Interprefy, released their own machine interpreting solution. This time, the response was much more muted. But now the precedent has been set. The days when human and machine interpreting were completely separate are over. But what does this mean for human interpreters and how we should adjust?

随后,另一家远程口译平台 Interprefy 也推出了自己的机器口译策划方案。尽管这一次,译员的回应已经温和许多,但先例已成:人工口译与机器口译相结合的时代,正式开启。这对于人工译员而言究竟意味着什么?我们又该如何适应这一变化?

Back to the facts

从事实出发

To understand what this means for human interpreters, we need to know a bit about how machine interpreting works. Machine interpreting uses one of two models. The first is the cascade model. This takes in speech, converts it to text, passes the text through machine translation, and then reads out the translation through automatic speech synthesis. The second is the rarer end-to-end model. This takes in sound, analyses it and then uses that to create sounds in the other language. There is no written stage.

要回答这个问题,我们需要先了解机器口译的工作原理。机器口译采用的主要模型有两种。第一种是级联模型,它接收语音,将其转换为文本,再将文本输入机器翻译系统,最后通过自动语音合成,读出翻译结果。第二种是较为罕见的端到端模型。这一模型直接接收语音,再基于分析生成目标语的语音,跳过了文本转换阶段。

The cascade model ignores emotion, intonation, accent, speed, volume and emphasis. It may be able to handle tonal languages but anything that cannot be represented in simple text is discarded. Cascade model systems are therefore very poor in situations that need emotional sensitivity, and clever uses of tone of voice, sarcasm, humour or timing. End-to-end models can, at least in principle, get over most of those hurdles. In theory, anything that can be heard can be processed. These models might also perform better with accents and faster speech.

级联模型忽略了情感表达、语调、口音、语速、音量和重音等要素。虽然它能够处理声调语言,但任何无法以书面形式呈现的信息都会被跳过。因此,级联模型在需要体察情感、语调、讽刺、幽默或节奏感的情境中表现不佳。相比之下,端到端模型至少在理论上可以克服这些问题。就其原理而言,只要信息可被接收,就可以被处理。因此,端对端模型可能在处理有口音和语速更快的语音方面表现更优。

Neither model can check if people understand the output, but they can be customised for different clients and fields. Neither model will do anything to adjust to social context, such as who is speaking to whom, differences in status and the emotional resonance of what is going on. Yet both promise to handle numbers, names and specialist terminology as well as, if not better than, most trained humans.

这两种模型都无法判断人们能否真正理解其输出内容,但它们会适应不同的客户和翻译领域。同样,这两种模型都无法根据社交语境调整语言表达,例如识别讲话者身份、区分不同的社交地位,或传递话语的情感。但是,它们都声称能够处理数字、专有名词和专业术语,并且表现可能与大多数训练有素的人工译员一样,甚至更出色。

In short, machine interpreting will soon beat humans at any kind of terminological and numerical accuracy we might care to measure. We will still beat them at customising our work for the audience, reading the room, speaking beautifully and pausing naturally.

简而言之,在术语和数字准确性方面,机器口译很快将在现存的任一衡量标准上超越人类。然而,在表达灵活、语境理解、措辞优美以及语音停顿的自然程度等方面,人工口译依然胜过机器。

Understanding client attitudes

理解客户心理

It should come as no surprise that the one video of a test of machine interpreting under semi-realistic conditions showed exactly what we might expect. In a video for Wired last year,1 two interpreters found that, while KUDO’s system was excellent at picking up specific terms, it did a poor job of knowing how to prioritise information and tended to find some unnatural turns of phrase.

一段对机器口译进行仿真情境测试的视频,其所呈现的结果正如我们所料。在这段《连线》杂志去年拍摄的视频中 ,两位口译员发现,虽然KUDO系统在识别专业术语方面表现出色,但在信息优先级的判断方面却表现不佳,而且常常会输出一些不太自然的表达。

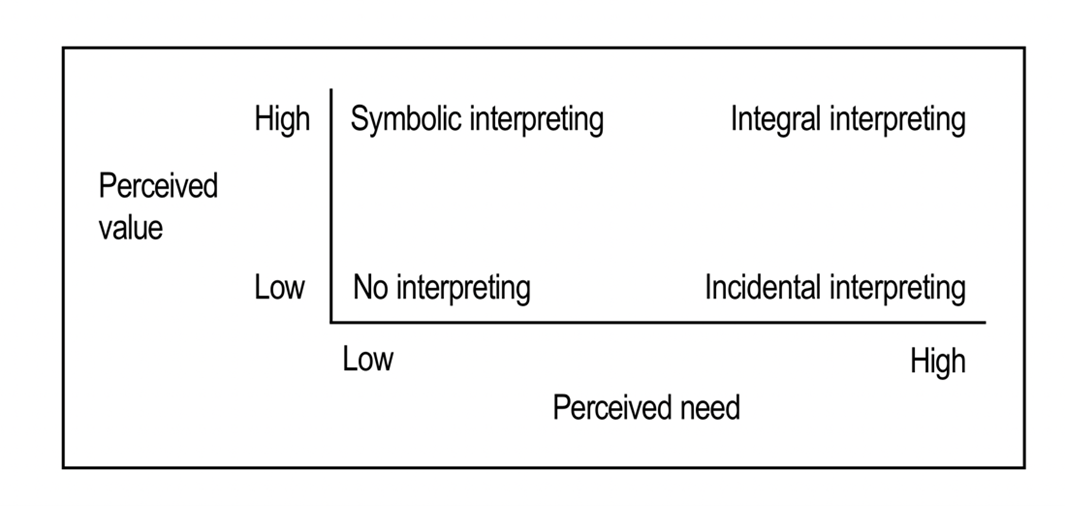

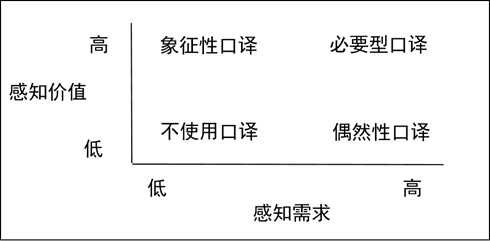

The overall result was that, while machine interpreting would do well enough as a stop-gap, it wasn’t reliable as a human replacement when it really mattered. But this gives us less reason to be joyful than we might think. This kind of nuanced analysis is foreign to most interpreting clients. We might happily talk about intonation, cultural nuance and terminology; very few of our clients do. To learn how clients think, we can use a simple model for classifying clients:2

总的来看,机器翻译虽能暂时应急,但在真正重要的场合下,其可靠性远不及人工翻译。然而,这一结果看似对我们有利,却并不如我们想象的那样乐观。原因在于,这种细致入微的分析对大多数口译客户来说可有可无。作为译员,我们可能乐于讨论语调、文化细微差异和术语翻译,客户却很少会关注这些方面。为了更了解客户的心理,我们可以使用一个简单的模型来对客户进行分类:

Some clients think that they need interpreting but wish they didn’t. They might hire interpreters to get a job done but they have no intention of working out how to integrate interpreting better into their workflows. These are the incidental interpreting clients – those who think we should just be able to turn up, sit in the booth, work and then go home, all with a minimum of fuss.

有些客户认为他们不得不使用口译,但内心觉得这是多此一举。他们可能会雇佣口译员来完成某项工作,但并不愿意花心思帮助译员适应工作流程。这类客户可被称为偶然性口译客户。他们只需要口译员按时到场,开始口译,完成工作,然后离开,所有步骤都做到极简。

Then there are clients who have a wonderful view of how powerful or politically important it would be to have interpreters. They hire us but do not actually use their headsets as they all speak the same languages anyway. This is symbolic interpreting. For those clients, as long as we look the part and are happy to appear to be working, it’s all good.

还有一些客户对口译持有非常美好的滤镜,认为配备口译员会显得很有实力或政治地位很高。他们雇佣我们,却并不佩戴口译耳机,因为实际上发言人都讲同一种语言。这种客户需要的是象征性口译。对于这些客户来说,只要我们看起来专业、愿意“假装”在工作,其他的都无关紧要。

Finally, apart from those who don’t think they need interpreting and don’t want it, there is integral interpreting. This is when clients think they need interpreting and really see the value of it for the future of their business or organisation. These clients see us as partners and want to work with us to make sure their event is a success.

除了那些认为自己不需要、也不想要口译的客户,最后一种就是必要型口译客户。这类客户不仅认为自己需要口译,还真正认识到口译的价值,并将其视为促进业务或组织发展的关键因素。这类客户将口译员视为合作伙伴,愿意与我们共同努力,以确保活动取得成功。

The most important thing to learn from this diagram is that different clients want different things and so are likely to make different buying decisions. Clients will always prioritise the success of their event or company over our careers. It is when they think the success of their event relies on close partnership with interpreters that they will buy our services.

分类图表中最重要的信息是,不同的客户有着不同的需求,因此也会做出不同的购买决策。相比于我们的职业发展,客户始终更重视活动或公司的成功,只有当他们认为活动的成功依赖于与口译员的紧密合作时,才会选择购买我们的服务。

To complicate matters, there are several possible solutions people can use when they need to understand someone who speaks another language. A few years ago, you were limited to interpreters, random strangers or phrasebooks. Nowadays people can choose from phone, remote and in-person interpreting, live-subtitling, and speech-to-text interpreting from humans, as well as apps, platforms, earpieces and automated subtitles, all using some kind of machine interpreting. In addition, professional interpreting of any kind has become more complex and the choices on offer have multiplied, with varying prices, strengths, weaknesses, potential and audiences. Like it or not, we now work in crowded marketplaces. So what will it take to thrive?

然而,现在的情况更加复杂,因为跨语言沟通方式变得更加多样化。几年前,人们的选择还局限于依赖口译员、偶遇的陌生人或简单的词典。而如今,他们可以选择电话口译、远程口译、现场口译、实时字幕、人工语音转文字,甚至还能使用各类应用程序、平台、智能耳机以及自动字幕等基于机器口译的工具。此外,各类专业口译工作也变得愈发复杂:市场中的选择日益多样化,译员价格、优势、劣势、潜力以及受众方面各有不同。无论我们是否接受,口译行业市场竞争已然十分激烈。身处其中的我们,如何才能脱颖而出,并获得成功呢?

Practical steps we can take

可行的措施

If we are no longer the only solution then we can’t afford to sell ourselves as if we were. Selling ‘accurate interpreting’ is now like selling a car and boasting that it has an engine. We can also no longer afford to sell ourselves as being so good it’s as if we weren’t even there. The people who want us to be invisible are the incidental interpreting clients, who are already thinking of moving over to machine interpreting.

既然我们已经不再是翻译服务的唯一解,那么就不能再像过去那样推销自己了。如今,将“精准的口译”作为卖点,就像在推销汽车时强调它有发动机一样平平无奇。我们更不能以“流畅到仿佛隐形的口译员”来宣传自己,因为希望我们“隐形”的,正是那些很可能已经在考虑转向机器口译的偶然性口译客户。

Instead, we need to talk more about the differences we make. What intelligent decisions do we make that machines can’t? What is the difference in terms of results between working with a human and working with a machine? We need to have answers to those questions that are convincing to clients.

相反,我们需要更多地强调自身的独特性:我们能做出哪些机器无法做到的智能决策?与人合作和与机器合作,会带来什么不同的结果?我们需要给出这些问题的答案,并有力到足以让客户信服。

We also have the possibility of using technologies to create better interpreting environments. How can we use machine interpreting and other AI technologies to improve the services we offer? Can we find ways to use AI to speed up or improve our preparation or to catch errors?

此外,我们还可以利用技术来创造更好的口译环境。我们如何利用机器口译和其他AI技术来改进现有的口译服务?能否让AI帮助我们提高效率,优化准备工作,或者检查错误?

Finally, it does seem as if we need to think about where we can specialise. For some, their specialism might be a rare language combination. For others, it might be some kind of meeting or domain. We already have specialist medical conference interpreters. Might we end up with interpreters specialising in meetings to do with law? Might we have specialist manufacturing interpreters or business negotiation interpreters or church interpreters, or specialists in construction or high technology?

最后,我们还需要思考如何强化自身优势。某些口译员可能善于处理生僻的短语,而其他人则可能擅长某种特定的会议或领域,例如,我们已经有专门跟进医学会议的译员。今后是否还会出现专门处理法律事务会议的译员,或是专攻制造业、商业谈判、教会活动、建筑行业乃至高科技领域的专业译员呢?

When we are not the only option, and especially when remote simultaneous interpreting (RSI) platforms are selling machine interpreting too, we need to give buyers a compelling reason to choose us. Having some kind of specialisation might give us the insight to know what extra information will convince clients as well as creating better interpreting.

当人工口译员不再是唯一的选择,特别是在远程同声传译(RSI)平台也开始提供机器口译服务的情况下,我们需要给客户一个选择我们的充分理由。拥有某种专长,可以帮助我们更好地了解客户需求,知道哪些额外信息可以打动客户,同时提升我们的口译质量。

These changes can’t be made overnight. Some interpreters might not manage to adjust. It is hard to specialise when most of your income goes on bills, food, light and heat. I know of colleagues who have left the sector. Honestly, I don’t blame them. There are lots of challenges for those of us who stay. We simply won’t manage on our own; we need to work together to support and encourage each other. Interpreting has just become much more competitive. We will only survive if we learn to cooperate with each other and not compete.

当然,这些转变并非一朝一夕能够完成。一些口译员可能无法适应这些变化,毕竟,当大部分收入都用来补贴家用时,我们很难再投入财力和精力去提高专业技能。我认识的一些同行已经转行了。说实话,我并不责怪他们,因为如果要坚持留在行业内,确实面临诸多挑战。我们无法孤身应对这些挑战,只有相互支持、携手合作,我们才能在这个竞争日益激烈的市场中生存下去。唯有团结,而非内卷,才能共建口译的未来。

Notes

1 ‘Pro Interpreters vs. AI Challenge: Who translates faster and better?’, Wired; https://cutt.ly/3wVvRAY8

2 Downie, J (2016) ‘Stakeholder Expectations of Interpreters: A multi-site, multi-method approach’. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Edinburgh: Heriot-Watt University

Dr Jonathan Downie is an interpreter, researcher and speaker. He is the author of Interpreters vs Machines and Multilingual Church: Strategies for making disciples in all languages.

乔纳森-唐尼博士是一名口译员、研究者和演讲者。他著有《口译员与机器》和《多语种教会: 用各种语言造就门徒的策略》。

This article is reproduced from the Spring 2024 issue of The Linguist.

Read the article in Chinese here.

Filter by category

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.