-

QUALIFICATIONS

- For Linguists Worldwide

- For UK Public Services

- Preparation

- Policies & Regulation

-

MEMBERSHIP

- Join CIOL

- Membership grades

- NEW for Language Lovers

- Chartered Linguist

- Already a member?

- Professional conduct

- Business & Corporate Partners

-

ASSESSMENTS

- For Second Language Speakers

- English as a Second Language

-

EVENTS & TRAINING

- CPD, Webinars & Training

- CIOL Conference Season 2025

- Events & Networks

- CIOL Mentoring

-

NEWS & VOICES

- News & Voices

- CIOL eNews

- CIOL Awards

- The Linguist

- Jobs & Ads

-

RESOURCES

- For Translators & Interpreters

- For Universities & Students

- Standards & Norms

- CIOL & AI

- All Party Parliamentary Group

- In the UK

- UK Public Services

- Find-a-Linguist

A case of two halves

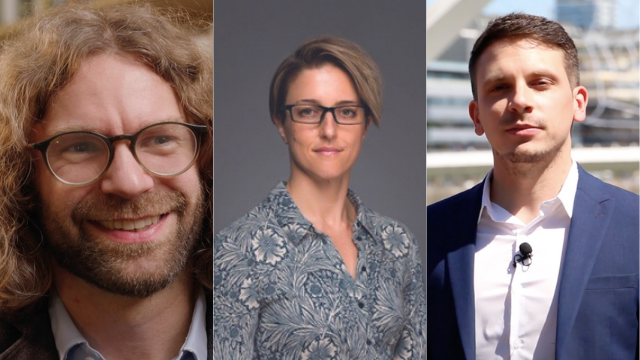

Sue Leschen and Rosalind Howarth outline their distinct perspectives of a murder case across two venues, as interpreters for court and counsel

Sue Leschen and Rosalind Howarth outline their distinct perspectives of a murder case across two venues, as interpreters for court and counsel

During a recent assignment on a murder case, Sue Leschen was booked ‘off contract’ (directly by the court and not by the Ministry of Justice’s outsourcing agency) as the ‘court interpreter’ and Rosalind Howarth was booked by the defendant’s solicitors. Sue’s role was to interpret for the defendant during the court hearing – whether he was in the dock or in the witness box giving evidence. Rosalind’s role was to interpret for him during his meetings with his barrister. As interpreters working on the same case we shared some of the same experiences, but our respective roles meant that we had different remits.

Shared experiences

This was a two-venue case: a crown court and a medium-secure hospital where the defendant was being held on remand, which was linked to the court via video. The defendant attended part of the trial in person and part by video link. From a practical point of view, having two venues in different towns made life difficult. On long-running jobs away from home, interpreters normally book a hotel to cut down on travel-induced fatigue, but that was impossible on this job, as we didn’t know from one day to the next which venue we would be working in.

Crossed wires between the court and the hospital as to the relevant venue, and even start times, occurred regularly. We were not always kept updated when the venue changed, which meant some hasty last-minute travel plans. Hospital staff also needed some notice of the venue, so they could arrange transport to take the defendant to court. In these circumstances, it would have been a lot harder working with a previously unknown interpreting colleague. Fortunately, we already knew one another through our professional network and had a good working relationship, so we were able to liaise about any changes to the venue or timings.

Rosalind tended to be more au fait with arrangements as she was in daily contact with the defendant’s barristers, while Sue was reliant on court booking staff, who weren’t always aware of last-minute changes themselves. Due to an administrative issue, Rosalind only started on day two and we didn’t find out we would be working together until the night before the first day in court.

A large group of the victim’s family and friends attended court every day, so when we were physically present in court we would seek out unoccupied consultation rooms, rather than stay in the public waiting room. This was in order to maintain distance and neutrality. However, it wasn’t always possible to find a private room, as they were often being used by barristers. It really highlights how little provision there is for interpreters (compared to lawyers) in court buildings.

Even though interpreters are as crucial to the criminal justice system as solicitors and barristers, we are not on a level playing field. One major issue is that we have nowhere to work or leave our bags, coats, laptops and other belongings. A separate waiting room for interpreters would have been really useful.

In many ways, being at the hospital was far easier. We were able to park there, so travelling was quicker and easier. We were treated very well by staff, who were friendly, helpful and patient when escorting us around the building. We were able to take phones and laptops into the conference room, although we were not permitted to use them in other parts of the building. The icing on the cake was the wonderful free refreshments that the hospital laid on during breaks and at lunch time.

Interpreting via video link at the hospital did, however, raise some challenges. In the conference room, the link and sound were generally very good, but as the room was located just above the delivery van entrance, we were occasionally affected by noise from outside. There was also some noise from the acute ward on the next floor. One day we were moved to a different room where the sound was extremely poor and we were unable to increase the volume. Sue struggled to interpret in this situation, so we moved back to the conference room the following day.

As interpreters, we often work on short assignments and are then able to draw a line under them and carry on with our lives. However, this trial lasted for more than two weeks and was all-consuming; we had little time for anything else. Sue missed the CIOL Conference while Rosalind struggled with childcare, particularly when the venue changed at short notice. It was difficult to keep up with our admin work, but we managed to check emails and make calls related to potential jobs during breaks. Requests for future work had to be carefully considered as it was uncertain how long the trial would last.

The traumatic stories and images that we were exposed to increased the feeling of fatigue at the end of each day. Along with the nursing staff, we woke very early each morning thinking about the case. We had flashbacks of crime-scene photos and videos. Pictures of a blood-spattered bed and video of the victim were particularly hard to deal with.

Sue Leschen, court interpreter

When the defendant was in the dock and not giving evidence, I had to make several requests to counsel and/or the judge and witnesses to speak up, slow down and/or use their microphone. When the defendant was in the witness box giving his evidence, I would stand next to him interpreting for long periods of time – sometimes more than 1.5 hours.

Occasionally I had to ask counsel to clarify their questions to ensure I had understood certain words and phrases, such as ‘pants’ (‘underwear’ or ‘trousers’?), if the meaning wasn’t clear from the context. Sometimes the defendant spoke very quietly, so I had to ask for repetition while trying not to interrupt the flow of his speech. Interestingly, the judge drew attention to “interpreter interruptions” in his notes for the jury and advised them to make “fair allowance” for this when assessing the defendant’s evidence.

On three occasions, the judge presented me with (previously unseen) lengthy documents and asked me to carry out on-sight translations there and then. Without a doubt, two court interpreters should have been allocated to a long-running assignment like this, but although conference interpreters usually work in pairs, the MoJ does not finance this sort of luxury.

I sometimes felt that the court treated the defendant with more respect than me. For example, the judge would allow comfort breaks for him, with my fatigue apparently being only a secondary consideration! At the secure hospital, the experience was completely different as we were able to share our experiences and coping responses with the nursing staff as professional equals.

Given my legal background and 20 years of legal interpreting experience, the legal terminology didn’t cause me any difficulties, but some of the physical and mental health terminology required research on my part. This included terms for certain body parts and medication brand names.

Having to interpret impact statements from the victim’s family at the end of the trial, wherein they described how the murder has affected them, was harrowing. Both the victim and the defendant were very young, and I experienced conflicting emotions about their two ruined lives. Interpreting intense sessions for half or full days with only short breaks left me feeling ‘brain dead’ due to total cognitive and emotional overload. Overall this was an unforgettable experience that will probably continue to haunt me.

Rosalind Howarth, counsel interpreter

This was a new experience for me, as I had not worked on a trial of this length before. While for Sue it was intense and short term during the trial weeks, for me it was a longer assignment, as I started working with the defendant a couple of months before the trial. From mid-January 2022 I was assisting counsel at regular online meetings with the defendant, I attended a case management hearing at the end of January, and I visited the secure hospital with counsel in advance of the trial.

The online meetings were very intense and some lasted for two hours. They were in the evening, which was tiring, and some of the details were traumatic. They did, however, help with my work during the trial, as I already knew a lot of details about the case and had a good idea of what to expect. I was also used to the way the defendant expressed himself.

The hospital environment was unfamiliar to me at first, but the staff were extremely welcoming and accommodating. One issue was a lack of access to the trial documents, known as the ‘trial bundle’, which was not always available at the hospital. There were also a few issues with displaying documents, such as the police timeline and photographic evidence, on the screen.

As the counsel interpreter, my job was arguably easier than Sue’s, as I didn’t have to interpret for long stretches during the court sessions. However, there were some long days and I often had to stay later to interpret for defendant/counsel conferences, either in the cells or in the conference room at the hospital. In court, it was hard to avoid the victim’s family and as the counsel interpreter I found this particularly difficult.

The trial was long, emotional and tiring, and the defendant struggled with this too, as he was trying to listen to both languages at the same time. Accounts were given by barristers, witnesses, the defendant, judge and victim’s family. Often the information was difficult to hear and process, and it was hard to switch off at the end of the day. I felt quite empty and numb when the trial finished, but it was a fascinating experience and one that I will never forget.

More

The Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), Incorporated by Royal Charter, Registered in England and Wales Number RC 000808 and the IoL Educational Trust (IoLET), trading as CIOL Qualifications, Company limited by Guarantee, Registered in England and Wales Number 04297497 and Registered Charity Number 1090263. CIOL is a not-for-profit organisation.